There, I put multimodality right into the title so if you want to skip it, please go ahead. Needless to say, this is one in a series of endless attempts to jam theories I am using for my PhD into any conceivable learning experience. This time, however, it does work (a bit).

Yesterday, my wife and I became tourists in London and went to the Tower of London and wandered around with the audio guides and learned as much as we were able to take in. It is an impressive place by historical standards and offers a window onto the changes of London over the last millenium like no other place I can think of. It sits just about two blocks from where I live now and for the last four months, I have wandered around, but not in, the imposing walls. For those who don’t know, it was built soon after William the Conqueror defeated Harold II at the Battle of Hastings, added to over the centuries, became a famous prison, a royal armory, and now resides as the home of the Crown Jewels and about a million tourists at any given moment. Either way, it is an aggregation of different architectural styles, different periods evoking different periods of British history. It is a warehouse of English memory encapsulated in material form. From a learning perspective, it is the definition of multimodality.

Multimodality: This Time I Define it

“an inter-disciplinary approach that understands communication and representation to be more than about language. It has been developed over the past decade to systematically address much-debated questions about changes in society, for instance in relation to new media and technologies. Multimodal approaches have provided concepts, methods and a framework for the collection and analysis of visual, aural, embodied, and spatial aspects of interaction and environments, and the relationships between these” (Bezemer, 2012, http://mode.ioe.ac.uk/2012/02/16/what-is- multimodality/).

“Multimodality approaches communication and interaction as something more than language” (Jewitt, 2009, p.1).

The Tower of London is a collection of visual, aural, embodied, and spatial artifacts cast together to project not only England, but also the power and role of the monarchy, the reach of the state, death, etc. It is an assembly of modes and artifacts that speak not only to the British people (although that is where I suspect it resonates the most-especially the long multimedia montage at the Crown Jewels section, which I suspect meant more to a British person as it fell flat with me), but to everyone. I can construct meaning by assembling the Tower of London behind the White Tower, casting the 12th against the 19th centuries. I can juxtapose those legendary ravens and their semi-circle swoops of flight with the strong, angular, grainy tiles of the battlements. I can do this just by moving left to right or up and down and all with my eyes and ears, arranging and assembling these visual resources towards some sort of meaning. Once I remove an element, the meaning changes. Removing Tower Bridge from the skyline removes the 19th century altogether from my gaze. The Tower of London is, or should be, the purview of Media Studies. It is an assembly of media on a grand scale.

That is learning as I see it and as it exists in motion in our material worlds, a rapid assembly and disassembly of learning resources based on some sort of convergence between time and space. It means something then and there that might not carry over into the next step or the next second. This is multimodality. And it is a skill we need to enhance or reclaim in age of endless media assembly; we are migrating towards the visual. This new landscape of communication is being accelerated by a shift towards using multiple modes in presentation and meaning-making, a shift towards the visual (Kress, 2000, p. 182). Some see this process of reclamation (repatriation?) as an imperative: “we, in the ‘West’, find ourselves singularly ill-equipped in the new landscape of communication, whether that is generally speaking, or institutional and non-institutional education (Kress, 2000, p.183, in Cope, Kalantzis).

Writing the Tower: The Role of Graffiti in Meaning-Making

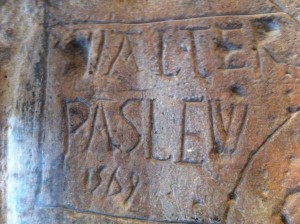

But strolling around the Tower of London yesterday, I felt both awed and distanced from what I was seeing. It wasn’t my history, nor was I able to actively use these learning resources all that much as it was a museum piece, the entire Tower. As well it should be as it needs to be preserved. But I began to spot various sections in the wall, in the bathroom, and in the infamous Bloody Tower itself that others had written themselves directly into the history of the Tower itself. They had made themselves a legacy and transformed themselves and their last thoughts into a learning artifact. Some had done it out of boredom, some seemed to be inspired, and some carefully considered their fate and their imprint. The effects were a hybrid of multimodality were the overall multimodal presentation, the Tower of London itself, was written on (or added to) to create meaning from the introduction of additional learning resources. Graffiti becomes an additional layer of semiotic content, an additional attribute for meaning-making. The Tower of London as an assembly of modes and meaning becomes a space for playful interpretation. Some of these scribbling were from people condemned to die; some were poetic verse. Others were simply a name and a date, a last gasp at the ether before shuffling off this mortal coil. That I stood here and that I too, existed. Graffiti reminds us that even signing a name can be art and can be beautiful.

Shakespeare and arrowslits

The first was someone who had written verse from Twelfth Night and signed their initials cryptically. It is found on the battlement wall facing the Thames next to an arrowslit.

If music be the food of love, play on-Shakespeare

SM

I actually love the juxtaposition of the arrowslit (from a wall from the 12th century), the Shakespeare quote (which has little to do with the military nature of that wall), and the cryptic initialing. All kinds of material to work with here. The language of power, the language of love and art, the language and power of anonymity cast against a cold London sky. This was good, but the graffiti from those locked in the Beauchamp Tower awaiting there fate. It was everywhere in the upper rooms, scratched with great skill and great patience at times, and with desperation at others. It was writing oneself into the records with only the wall itself as an instrument at almost the moment where these materials, this history, and this environment were about to cease to be useful (this is my euphemism for death).

I thought these presented an interesting wrinkle into how I envisioned multimodality. I tend to see it as an assembly of media and modes by an individual for communal positioning and purpose. I present my knowledge so we all can learn. However, at times it is our collective writing onto each other and onto our sacred objects that produces meaning. It is an assault on that living, breathing, imposing symbol of history and culture and significance by using whatever tools happen to be at our disposal. Adding, etching, carving, dirtying (?) to an existing multimodal representation with our own take on our relation to it. To collaborate even in spite.

I am not advocating spraying graffiti over all our precious monuments as they are relics for everyone, not just for the individual. But I am advocating for an ability to write to places (social media, people, not physically), to leave a reminder, a note, a message saying I was here and I juxtaposed this against this and this made sense to me. A living history not unlike the connection I felt with the man etching his simple name and year on the cold, stone wall in London five hundred years ago. To see more of my photos from the Tower of London, click here. To learn more about the graffiti in the Beauchamp Tower, click here.