African Rock Art as Nodes of Sanctuary

I am heading off today for a whirlwind of travel through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio to visit family and friends, so perhaps in anticipation of that my thoughts turned towards travel and mobility. I had read a relatively recent story about the display of the oldest known portrait at the British Museum as part of the exhibition Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind.

It reminded me of when I worked on African Rock Art as part of this database on African materials. From that prior experience, I learned from Dr. Benjamin Smith from the University of Witwatersrand (Rock Art Research Institute) about rock art and how it represented the first attempts by humanity to present understanding conceptually. These were our first forays into non-verbal communication (the first recorded ones, at least). In the presentation below that we put together from a live broadcast (circa 2007, I believe), Dr. Smith highlights photographs, re-drawings, and research about rock art created by Pygmy, San, and other indigenous peoples. The presentation includes a discussion on discovery tactics for scholars and students interested in using rock art content in their teaching and research. It is long (45 minutes) but incredibly fascinating. I was enthralled when I recorded it. If you like it, be sure to go download it for yourself at the Aluka site. Apologies for the audio quality, but it was done via the phone (if I remember correctly).

[vimeography id=”4″]

It had me thinking about artistic representation and the profound effect that representation had on the human psyche and our available mechanisms for communication. Once we began representing our communication visually, there was no turning back. Formalized languages and alphabets emerged from these etchings. Dr. Smith alludes to this, but it also opened my eyes to the encapsulation of motion and mobility found in this rock art, how travelers, hunter/gatherers would have used these images to find their way through hostile territory, to know that a particular cave was safe for lodging, that others had been there before. They were waypoints on a sea of otherwise hostile terrain, connections to the nodes of our burgeoning humanity and communities. These artistic representations would have followed us out of Africa, into the plains of Yemen and Saudia Arabia, throughout Europe, Asia. There would have been art left behind to let us know that so and so passed here and was safe. Like all communication, it would have been reassuring.

Ivory Sculptures, Emotional Content, and Mobility

So that was the bridge that allowed me to approach this story about the 26,000 portrait, the oldest known portrait in the world, found in what is know the Czech Republic. It is a portrait of a woman carved in ivory and it is relatively well-kept. Historically, it is profound as it dates our development into these representations earlier than previously thought. Communities at this time were generating their own representations, their own projections of identity, self, beauty. That is significant and it involves a transition to a more active ownership of knowledge and legacy.

From a mobility perspective (more anthropologically), it demonstrates the portability of emotional content, a precursor to carrying a photograph around in a wallet. This sculpture is portable (by the standards of the day) and could have traveled with the creator, or the someone who commissioned (not sure what commissioning looked like 26,000 years ago) it. It could have been a figure of worship, a revered spirit that bound together sprawling clans and communities slowly meshing towards larger identities. It would have moved with the people. This sculpture predates or runs parallel to agriculture itself, which means that the community that produced this would have been, most likely, a nomadic, mobile one. It followed with them or with someone on their travels.

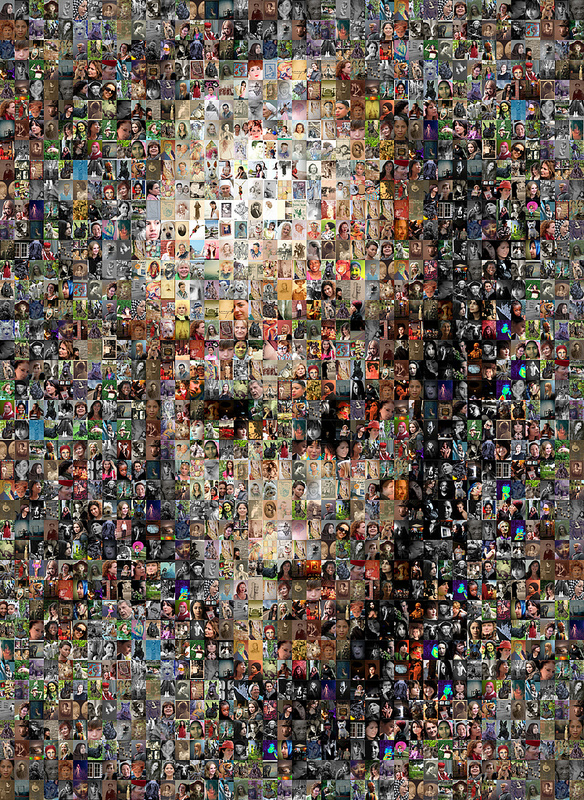

Emotionally, it provides evidence that someone 26,000 years ago thought this woman was so beautiful or so powerful or both to record for posterity. To have a likeness to carry with them wherever they went. It could be a gesture to a god, a deceased leader, noblewoman, wife, sister, mother. She sat there as the artist whittled away the ivory, slowly capturing as best as possible the contours of her face, the depth of her eyes. It is the gaze of aesthetic representation and it is captured for all time. So I started to remix the image as best as I was able, adding layers of aggregate images of female portraits, some of the present, some of the past. This sculpture was the first (known) step towards representation and with it the myriad positives and negatives of that conceptual approach. Objectification didn’t start with this sculpture, but it is captured by it. To represent, in some small measure, is an attempt to capture the fleetingness of being. But it is beautiful and she is beautiful and someone, so very long ago, thought so as well.