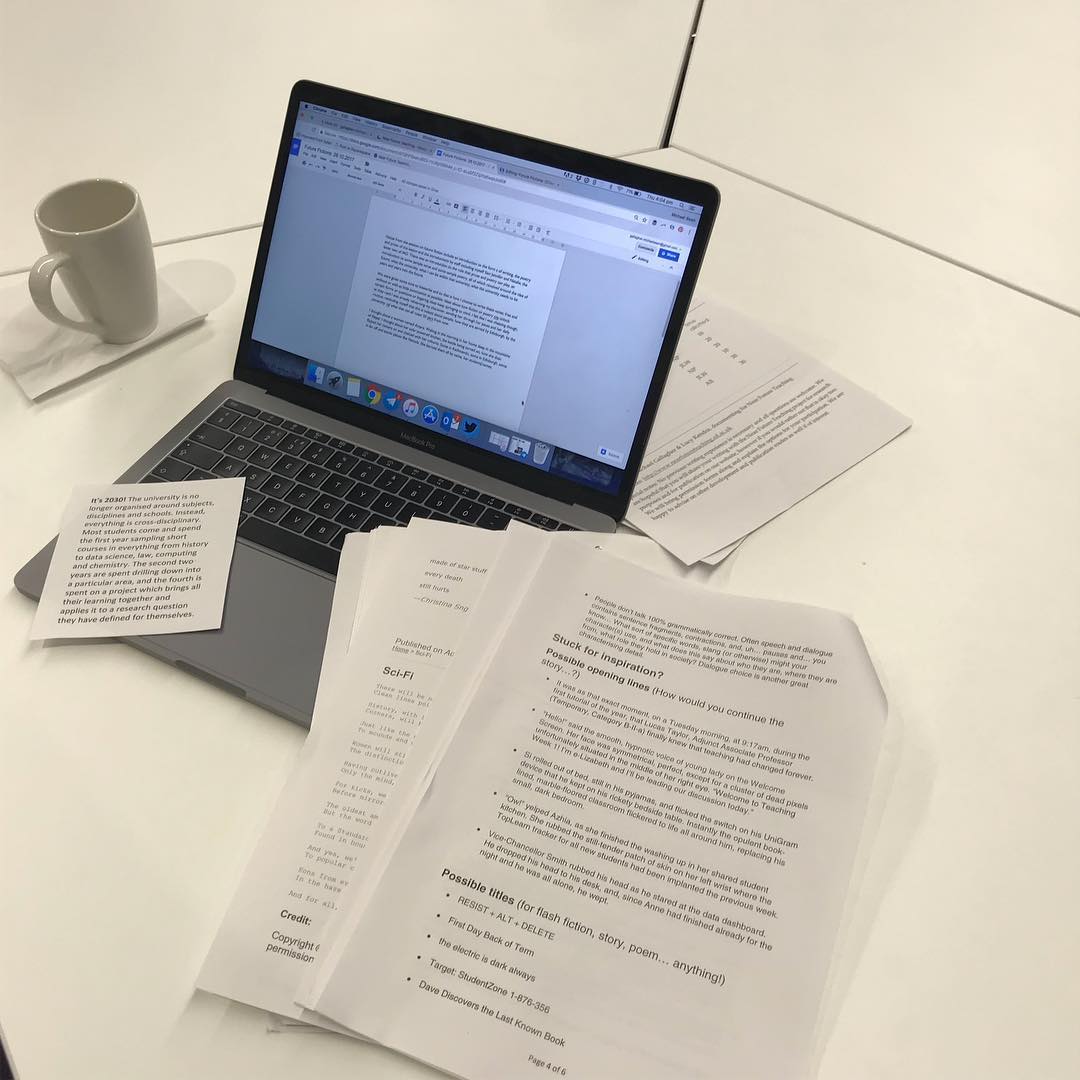

We have had three events this past week for the Near Future Teaching project here at the University of Edinburgh. All well attended, well received, and ultimately all generating well positioned intentions of what the future of the university should be. We learned how blockchain works and how it might be applied to education, we learned with VR, AR, and 3D printing, and we learned how fiction can unlock spaces for exploring imagined scenarios of what we want the university to be for us in the future.

I’ve embedded the Storify posts below for review and these can all be found on the project site. As far as my own outputs, I was drawn to the Future Fictions event as I haven’t written creatively for years and years (although I would certainly self-identify as a writer) so writing on queue around particular prompts about future teaching and learning was challenging. However, once I pushed back the initial resistance in my own mind, knowing full well that this would be read in front of others at the end of the session, (and still trying to fulfil my primary purpose of taking field notes of the event for research), I ended up fleshing out a character I had started in another space and gave her more and more agency here towards her own future. It is rough and clumsy but it is an honest representation of what emerged from those 30 minutes of free-writing and hasn’t been edited since. This is the future I want to work towards, the high stakes we should be all striving for, this level of agency in our students, our community of learners. I suppose this is what I want to see in the next 30, 40, 50 years. The blockquotes are simply to show Amara is talking or thinking.

Amara and the Future of Education at the University of Edinburgh

I thought about a women named Amara. Waking in the morning in her home deep in the mountains of Nepal. I thought about her solar powered kitchen, the kettle being turned on, how she then flipped her camera on and chatted with her cohorts. Some in Kathmandu, some in Edinburgh, some in far off and exotic places like Nevada. She learned them all by name, her students names. This is her week in the rotation, where she teaches her cohorts and her professor what she knows. Hard to whittle it down to something manageable. But that is what communication is, she sighs. Nuance and brevity. Tempered. Critical. Her camera projects her walking through the kitchen, attending to her basic tasks, waking the children soon. It is intimate but all her other classmates are the same. Walking around in various states of disrepair. Disheveled. Waking. Some have been up for hours, some are soon heading to sleep.

I can’t believe it’s 2030. I can’t believe I am 35. I can’t believe how much it took to get this lesson together. I interviewed the mothers, asked them about how they go about learning. How they learned to read. To write in the first phase of this project back in 2020. Told me their stories. My mother taught me, then years later I taught her the media I make my living from now. She sends her missives to family all over the world. The narratives, the methods, the stories, the technology. The maintenance of that technology. Oh my the maintenance. Documenting our stories, stringing them together, archiving them, unleashing them, our dialects, our pauses and imperfections. The blemishes. I want the world to know. I am a part of this.

Amara assembles her learning and presentation space. Her camera is still on as she organises the data, converts it to sound, tweaks it so as to be pleasant. A soundscape of her learning. She doesn’t mind people watching. She likes the messiness of it all. She hears sounds from the river down the way in village in Nepal. Sounds of data from Edinburgh, churning through, the din of traffic, the churn of data. She learned how to do this, to make language from this. Now she is teaching everyone how to do this. She assembles her other screen. The visual scape. Her daughter tugs at her shoulder.

Sit with me. Let me show you what I am doing. I am showing them, go ahead and wave, showing them what I know, teaching them how to make it themselves, with their own sights, sounds, and data. What data are you producing now my love? Your heart is beating, your mind is thinking, the electricity is powering that kettle. Someone is growing vegetables. Someone is selling their products. Somewhere, people are recording their memories, their ideas. Think on it while mommy teaches.

Amara compiles data from law, from education, from the sensors scattered throughout the village that measure moisture, seismic activity, that measure remittances coming from family overseas. Measures the remittances she sends back. Money flows. Electricity flows. Flows of time and learning. All of it is counted somehow, or measured, or just noticed. Amara’s job is to show them how to pull this altogether, to temper it. To let the patterns speak in different ways. She has done several of these classes this week, a project that will solder her place at the University of Edinburgh. A graduate yes. Always a graduate. A teacher as well. Faculty. A contributor, a critical vision, a part.

Charlie, your microphone is on. I can hear the static….Excellent. Thank you. Let’s begin…My name is Amara, as you know, and the University of Edinburgh, my university, is this…

Makerspace, future fictions, & blockchain: notes from this week’s @NearFutureTeach events & my fictional Amara… https://t.co/lcrTZBB6e7