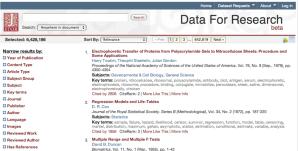

I work with Data for Research (DfR) quite a bit as part of my professional duties and wanted to pass along some observations I had regarding its application as a learning tool. DfR is a set of web-based tools for selecting and interacting with content from the JSTOR archive. The service also provides the ability to obtain data sets via bulk downloads or using a REST API. Basically, it takes the lion’s share of what is in the JSTOR archive and makes it available for data analysis (in large data sets), exposes word collocations (bigrams, trigrams, etc.) word counts, all charted over a course of time. What is significant is more the scope of the archive for possible research topics. Close to 500 years worth of academic data, 7 million+ articles, billions and billions of words of text in 50+ disciplines.

The ability to extract the most common terms used in these texts say for a given time period in a particular discipline (and subdiscipline) with certain search terms is remarkable. I, as a learner, can see the most common geographical terms used pre and post-World War I, chart the differences over time of a particular term (glasnost, anyone?), monitor and track the ephemerality of academic terminology over a course of time (when did consumption become tuberculosis?). There is much more to be done with it, obviously, including downloading massive datasets for larger analysis. But for learners, it provides quite a bit.

Navigate entry into a new discipline with vetted jargon

Learners view new disciplines, specifically highly specialized ones, as foreign territories. Academically, everything is designed to affect this notion of other, unique, particular. The terminology, the process, the authoritative entity, the vetting process, even the collaboration has the unique stamps of disciplinary particularity. As teachers, we are doing a disservice to our students by thrusting them into these discussions without the language to engage and interact. In complex knowledge territories, it helps to have a primer, a decoder ring. This isn’t necessarily designed to mitigate the unnerving elements of foreignness as those can be pedagogically fertile. But primers are buttresses against overload and eventual withdrawal. Complexity can be overcome with language, language as a vehicle for sensemaking (for drawing one’s own conclusions in unfamiliar terrain). Academic language is highly specific, so why not provide that at the onset of the learning journey. DfR helps me do this by isolating the most commonly used terms in any discipline or subdiscipline at any given time. See below for the document of the most commonly used terms in History from 1980-2009. Have your learners conceptualize these terms before exploring; what key concepts and ideas are prevalent and why do we think they are of such importance?

Track the ephemerality of an academic meme/idea

It isn’t so much that the ideas themselves die out (some do), but rather I find that it was a pivotal shift in my maturity as a learner when I embraced the notion that significance is the convergence of an idea at a time in a place. All three elements must be there and when one element, time especially, is adjusted, the potency of the idea is affected. So, academic language reflects this in its choice of vocabulary. Words that mattered once and don’t as much, perhaps used to identify a fleeting, yet potent, meme. Glasnost. Pan-Africanism (which waxes and wanes quite a bit). Distance learning (I hope). Learning that the complexity of an idea is often exhibited through the fleeting accuracy of words we use to describe it. They are almost dated as soon as they coined.

With DfR, I can track this a bit over time. I can see when the typeset whofe was corrected to the modern whose (literally the old typeset was replaced with a proper s). I can track the entry of foreign vocabulary into the English language (sushi came later than I thought). A tool for the empowered learner to sleuth their way through academic discourse. Trace when it fell into favor (and more commonly, out of it). Shift the learner’s impression of language as static towards a dynamic enterprise of ephemeral convergence.

I will right away snatch your rss feed as I can’t in finding your email subscription hyperlink or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly permit me recognize in order that I may subscribe. Thanks.