I have been spending some time with two reports recently that have me thinking a bit about the outcomes we in the ICT4D and digital education fields are looking for in our work. Both challenge some of my perhaps idealistic beliefs that the technology could enable positive impact (which in some cases it has) in resource deprived environments. I can point to enough evidence there to suggest that is the case, but it isn’t evidence that scales very well. A success story here or there tied to a regional context. Some data to suggest increased literacy levels or greater access to health care. Overall, a tick upwards towards meeting SDGs, a small triumph in and of itself.

Technology has a role in some of these developments. Yet, the churn from its wake complicates and often disrupts domestic developments in civil society: teachers, home-grown industries, democratic governments. A certain mobility has been let loose that is difficult to contain. It can be good or bad depending on the context, depending on the time of day I seem to be thinking of it. A complicated impact.

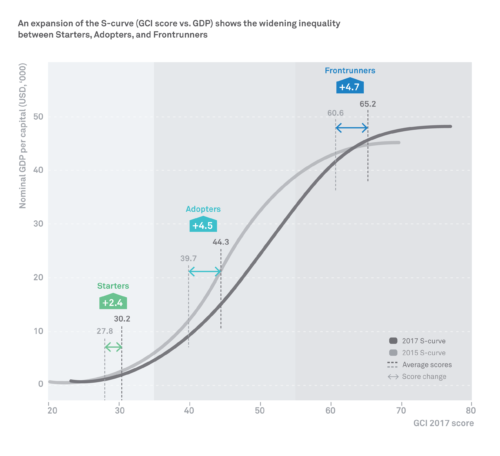

The first is Huawei Global Connectivity Index (GCI) 2017, a study “that shows how countries are progressing with digital transformation based on 40 unique indicators that cover five technology enablers: broadband, data centers, cloud, big data and Internet of Things. Investing in these five key technologies enables countries to digitize their economies. Through centralized planning, potential connectivity can be fully leveraged and ICT capabilities can support positive growth of national economies.” The link here is clear (at least as presented): greater technological penetration and adoption leads to positive growth of national economies. Yet, as suspected, that growth is unequal. While many LDCs have certainly benefited from the growth of their technological sectors, the digital divide that has plagued us for so long is widening. Production and adoption cycles are becoming so accelerated that it is difficult, if not impossible, for Ethiopia (for example) to conceivably jump from the development of their mobile sector to anything remotely related to IoT, if we view these as opposite ends of sophistication along the technological spectrum. Some of these rungs along the technological ladder can be leapfrogged for sure, but leapfrogging into some sort of competitive role in these emerging technologies is beyond optimism. The data from Huawei notes the widening inequalities in the rates of adoption for Starters, Adopters, and Frontrunners as seen in the graph below.

While these increasing gaps are worrisome, more importantly is the capital shortfall that limits competitiveness in the next technological lifecycle. As the national GDP is double for Frontrunners than Adopters and quadruple that of Starters, we have a growing gap not only in access to the technologies but the capital and increases in GDP that these technologies purport. I learned a new term as well: the Matthew Effect– “the sociology theory that in effect states: Big investors in connectivity and ICT Infrastructure at the top of the S-curve should also show significantly stronger GDP per capita than those at the bottom of the S-curve.” Essentially it speaks to “accumulated advantage”: the advantages will compound over time and rarely leak to the lesser party.

Yet, we have seen domestic tech-based industries sprout in ICT4D, tech hubs emerging across sub-Saharan Africa, all predicated on local need using appropriate and available technologies, all suggesting some potential upward tick of GDP, of access to capital, of domestic investment. That is what I want beyond having Zambia suddenly become the world leader in Bitcoin or something. I want domestic capacity for domestic issues, regional capacity for regional markets, and so forth. Meaningful scale. And this extends, of course, to education.

I have to thank Derek Moore for tipping me to the next one as I missed it altogether. It is the Business of Education in Africa from Caerus Capital. It focuses on private education but I believe speaks to, or is a direct result, of the widening gaps suggested in the Huawei. In this case, it is the lack of capital for investment in education. It is not a problem specific to Africa by any stretch of the imagination. Governments the world over are walking back their commitments to such expensive social programs, messy as they are in their processes and outputs. The report as described by the authors:

…drew on available research, primarily from the 15 largest countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) by population, to build a picture of the current landscape for private education in SSA. The Phase 1 report (which was limited in circulation) was completed, in most part, to provide input into “The Learning Generation” report published by the International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity…This report builds from this first phase. It involved detailed, on-the ground research in six countries between July 2016 and February 2017: Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa (larger and relatively more established Anglophone markets), Ethiopia (a fast-emerging economy to watch), Senegal (a promising Francophone market), and Liberia (a post-conflict, resource constrained smaller country). The research has involved nearly 260 interviews and consultations with SSA and global education sector leaders representing donors, private providers, investors, and government officials; covered more than 135 private not-for-profit and for-profit education case studies; and assessed the regulatory context for education.

This report is complicated in that lack of capital is indeed a very real issue for countries looking to invest in their own education sector, to satisfy the educational needs of a very young population. No small task. Yet, this report is also, I believe, an instance of accumulated advantage. Capital finds markets to invest and then strives to create optimal conditions for these investments to flourish. Policy changes to lessen restrictions on private education. Loosening restrictions on curricular responsibilities, hence the Bridge Education’s teach by numbers approach (recently and thoroughly dissected by Maria Hengeveld). Branch campuses to compete with domestic higher education (Korea’s KAIST in Kenya being but the tip of the iceberg here). I would love to see greater teacher training provisions or support for organisations that do this, like Africa Educational Trust, but I am doubtful as there is little return on that investment. The target here are the students and the conduit for this is the technology.

The takeaways from the report itself:

- Policy challenges are present, but they don’t change fundamentals — the outlook for investors is very strong.

- A window exists for proven global education providers to enter the African education market, with the proviso that they must contextualize their approach to Africa.

- There is significant potential for local conglomerates to become education providers, and this type of diversification is observed in other emerging markets.

- Africa serves as an innovation platform and can be leveraged to develop solutions for global replication.

Global education providers and the provision that they must contextualize their approach to Africa (however defined). Africa as an innovation platform for global replication. Local conglomerates as education providers (school systems ARE local conglomerates!). This is the language of capital and should be seen as such. Not inherently a negative but also we need to be aware that there are fundamental differences between what education is attempting to do and what capital wants it to do. These are not the same thing. Without the local capacity driving local innovation and development, without this being driven by local policy and local political will and protections, this is a poacher’s market. Accumulated advantage allows these private investors to swing and miss. Local educational systems can’t afford to miss at all.

Digital divides and accumulated advantage #adultedu #edutech https://t.co/A2lzDI9Kar

Digital divides and accumulated advantage: Huawei Global Connectivity Index & Business of Education in Africa… https://t.co/xussIeWLYY

Hello Michael,

You posted an interesting comment about our teacher training with a link to this article on our website. Was curious to talk more about your experience with digital education for development. Is there an email I could reach you at?

Digital divides and accumulated advantage: Huawei Global Connectivity Index and the Business of Education in Africa… https://t.co/AflKMfBwo5