Building on my previous post on using Pinterest for classroom use for writing, this post is about using Thinglink (or some equivalent service) for translating images into text. This idea was inspired by Anne Rongas of Finland, with whom I worked as part of a workshop I conducted there on mobile learning and field activities. She demonstrated Thinglink to me (I believe it is a Finnish development) and I have found it quite useful as an instructional and learning tool. So this post is simply about how I go about doing that.

The underlying theoretical assumptions about the type of learning taking place here are much the same as those mentioned in the previous post. That is, switching modes broadens the learning environment and develops skills/literacies that are highly relevant to an age where more and more of meaning is being expressed outside of text. Much of this is encapsulated in Multimodality (Kress, Bezemer, Jewitt, et al) and much is encapsulated in a smattering of other cognitive theories of learning (Vygotsky’s socio-culturalism, materiality of Fenwick and Farman, etc.). Not to even to mention the media studies aspects of this. Ultimately, the gist is that walking an idea across modes is extremely beneficial to learning. To start with an image, to scaffold an activity that allows learners to interpret it, identify the salient characteristics of it, analyze and re-assemble them into another mode, and then draft a related composition in that new mode. This is learning across a range of literacies and learning that is highly relevant to making conscious a process that is often reflexive.

It is doubly useful for those studying in a second language, or in the case of my students, those studying to be linguists, interpreters, or translators. It allows for language to be transferred across modes (and across contexts) and to be used in authentic settings. It allows this to happen through the resilience of the learner’s approach to meaning making, that is it forces on them an understanding that meaning is to be aggressively crafted through an aggregation of ‘things’. Meaning sometimes is found or discovered; meaning is sometimes crafted or forged. Rarely are these radically ideas separate from one another. So, I like working with images for these classes as they provide a fairly broad canvas for analysis and interpretation. One can isolate only the cultural elements or the emotional elements, or the material elements (even techniques, styles, etc.). One can personalize them as a means of interpretation (what do they evoke, or remind you of?) or link them to topical, social, or economic currents. Which is why Thinglink is so useful in this context.

Thinglink: Sensemaking in the early stages

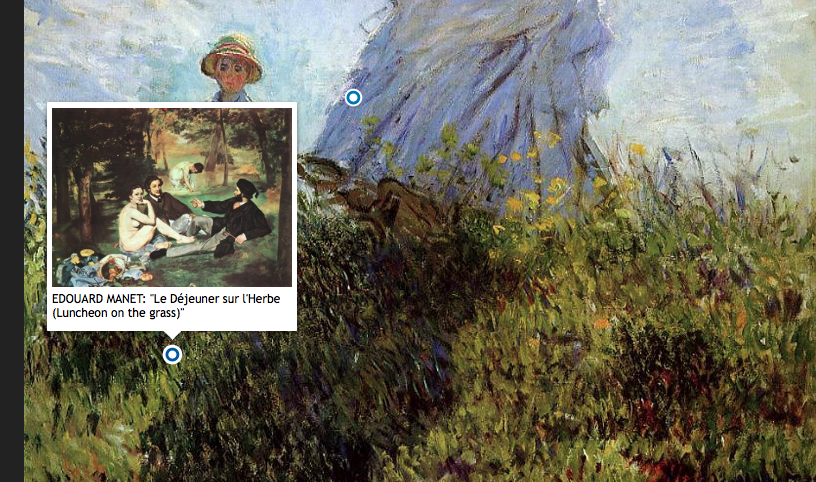

So Thinglink allows you to simply embed context (or links) into the image itself. Like taking notes on a famous painting. Basically it is like tagging something for later use. Students can spend time with the image, add thoughts and observations, and, most importantly, begin to make associations with other ‘things’. So, for example we have below Monet’s La Promenade (1875), a beautiful painting of Monet’s wife and son caught in ephemeral context. The sky, the wind, the grass, all in motion.

So, one possible exercise is to introduce the painting and recommend a particular point of analysis that you would like your students to pursue. This is there window into context. For those students with more of an artistic background, it could be merely a process of associating elements of the painting with other paintings. Much as I did in this interpretation.

So, the first stage of understanding in the above example is through association with other known things. This is a scaffold. It bridges the known and the unknown (I suppose that is what all bridges do). From there, it is a matter of extrapolating the tags/links, slotting those into categories (perhaps through other imagery), outlining and drafting into text. I think this intermediary step of a hybrid image/textual interpretation is very productive for the imagination and for organization. Students begin to imagine alternatives to linear presentations (invariably leading to the question of “Why do we have to write a text-based essay?”) and begin to question the standard format of essays as a means of interpretation. Further students begin to see the salient ‘bits’ of larger compositions. It is one image, yes, but it is a collection of parts, artifacts all. There is lighting, color, gaze, setting, style, technique, emotional context, symbolism, etc. All of these can be foregrounded with a prompt from the teacher. All require mental agility on the learner. All in all a very productive activity and one with tangible outputs (if you require those for portfolios and the like).

I also enjoy this as you can use one image and take a deep dive with it, across disciplines (art, history, economics, sociology) and across narratives (personal, socio-historical, artistic or otherwise), and from personal to social. Each angle requires a rethink of what is known and unknown, what is foregrounded or backgrounded depending on the means of interpretation. Useful skills for any interpreter, media type, or even lifelong learner to have. For the second language student, this identifies vocabulary and activates it across a series of contexts. I find retention is incredibly improved when associated with visual artifacts across more than one context. One fairly simplistic example can be found here and below. Simply having your students identify vocabulary from the painting filtered through a particular interpretative lens. For example, this one is merely identifying emotions or feelings being generated by the painting itself.

In terms of how I pragmatically use tools like Thinglink and Pinterest, it is mostly outside of class. We spend time in class introducing the image, or series of images. We spend time in class circulating the interpretations for further interpretation. It can be used in class, although I don’t. I spend more time in class introducing the mechanisms for interpretation. The framing of the discussion, the research questions we want to answer. I let them run with it in groups or alone. I encourage, but don’t require, them to post it for all to see (via a blog). I monitor the progress, but try to avoid any assessment at this stage of interpretation. Merely advancing the interpretation is sufficient progress. This activity sometimes leads to text-based writing and sometimes it doesn’t.

[…] Padlet or Thinglink as a mindmap of course concepts and emerging thinking along with a design […]

[…] Padlet or Thinglink as a mindmap of course concepts and emerging thinking along with a design rationale: could do that […]